Published on Apr 02, 2024

Cars are immensely complicated machines, but when you get down to it, they do an incredibly simple job. Most of the complex stuff in a car is dedicated to turning wheels, which grip the road to pull the car body and passengers along. The steering system tilts the wheels side to side to turn the car, and brake and acceleration systems control the speed of the wheels.

Given that the overall function of a car is so basic (it just needs to provide rotary motion to wheels), it seems a little strange that almost all cars have the same collection of complex devices crammed under the hood and the same general mass of mechanical and hydraulic linkages running throughout. Why do cars necessarily need a steering column, brake and acceleration pedals, a combustion engine, a catalytic converter and the rest of it?

According to many leading automotive engineers, they don't; and more to the point, in the near future, they won't. Most likely, a lot of us will be driving radically different cars within 20 years. And the difference won't just be under the hood -- owning and driving cars will change significantly, too.

In this article, we'll look at one interesting vision of the future, General Motor's remarkable concept car, the Hy-wire. GM may never actually sell the Hy-wire to the public, but it is certainly a good illustration of various ways cars might evolve in the near future.

Two basic elements largely dictate car design today: the internal combustion engine and mechanical and hydraulic linkages. If you've ever looked under the hood of a car, you know an internal combustion engine requires a lot of additional equipment to function correctly. No matter what else they do with a car, designers always have to make room for this equipment.

The same goes for mechanical and hydraulic linkages. The basic idea of this system is that the driver maneuvers the various actuators in the car (the wheels, brakes, etc.) more or less directly, by manipulating driving controls connected to those actuators by shafts, gears and hydraulics. In a rack-and-pinion steering system, for example, turning the steering wheel rotates a shaft connected to a pinion gear, which moves a rack gear connected to the car's front wheels. In addition to restricting how the car is built, the linkage concept also dictates how we drive: The steering wheel, pedal and gear-shift system were all designed around the linkage idea.

The "Hy" in Hy-wire stands for hydrogen, the standard fuel for a fuel cell system. Like batteries, fuel cells have a negatively charged terminal and a positively charged terminal that propel electrical charge through a circuit connected to each end. They are also similar to batteries in that they generate electricity from a chemical reaction. But unlike a battery, you can continually recharge a fuel cell by adding chemical fuel -- in this case, hydrogen from an onboard storage tank and oxygen from the atmosphere.

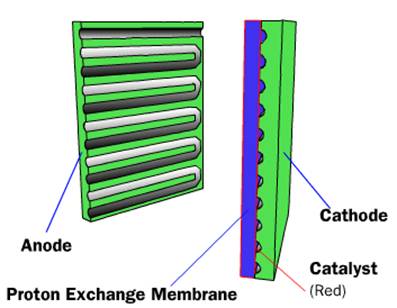

The basic idea is to use a catalyst to split a hydrogen molecule (H2) into two H protons (H+, positively charged single hydrogen atoms) and two electrons (e-). Oxygen on the cathode (positively charged) side of the fuel cell draws H+ ions from the anode side through a proton exchange membrane, but blocks the flow of electrons. The electrons (which have a negative charge) are attracted to the protons (which have a positive charge) on the other side of the membrane, but they have to move through the electrical circuit to get there. The moving electrons make up the electrical current that powers the various loads in the circuit, such as motors and the computer system. On the cathode side of the cell, the hydrogen, oxygen and free electrons combine to form water (H2O), the system's only emission product.

In a hydrogen fuel cell, a catalyst breaks hydrogen molecules in the anode into protons and electrons. The protons move through the exchange membrane, toward the oxygen on the cathode side, and the electrons make their way through a wire between the anode and cathode. On the cathode side, the hydrogen and oxygen combine to form water. Many cells are connected in series to move substantial charge through a circuit.

In a hydrogen fuel cell, a catalyst breaks hydrogen molecules in the anode into protons and electrons. The protons move through the exchange membrane, toward the oxygen on the cathode side, and the electrons make their way through a wire between the anode and cathode. On the cathode side, the hydrogen and oxygen combine to form water. Many cells are connected in series to move substantial charge through a circuit.

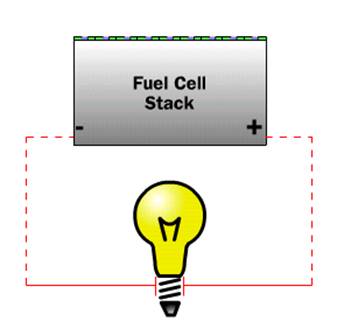

One fuel cell only puts out a little bit of power, so you need to combine many cells into a stack to get much use out of the process. The fuel-cell stack in the Hy-wire is made up of 200 individual cells connected in series, which collectively provide 94 kilowatts of continuous power and 129 kilowatts at peak power. The compact cell stack (it's about the size of a PC tower) is kept cool by a conventional radiator system that's powered by the fuel cells themselves.

| Are you interested in this topic.Then mail to us immediately to get the full report.

email :- contactv2@gmail.com |